A Painted World

This near forty-year retrospective of Alan Robb's painting is composed of a selection of works dating from 1974 to 2012. It is an overview that brings out continuities that, beneath all changes of subject and formal development, give coherence, identity and personality to his work. The exhibition makes it plain that he stands in that post-war North East Scottish tradition which is founded on resolved pictorial ideas, on drawing, on tonal painting and restrained handling. This deep investment in a set of painterly values was absorbed first at Gray's School of Art, Aberdeen (1964-69) then capped by three years at the Royal College of Art (1969-72) where the conceptual foundations of his work (above all) were challenged and strengthened. He was left with an adaptable and robust practice perfectly suited to his temperament and personality. His later professional teaching experience and exposure to contemporary art and to the masters of the past consolidated his allegiance to aesthetic and intellectual clarity. His titles again and again tell us that he is driven not only by the eye but also by the idea.

This near forty-year retrospective of Alan Robb's painting is composed of a selection of works dating from 1974 to 2012. It is an overview that brings out continuities that, beneath all changes of subject and formal development, give coherence, identity and personality to his work. The exhibition makes it plain that he stands in that post-war North East Scottish tradition which is founded on resolved pictorial ideas, on drawing, on tonal painting and restrained handling. This deep investment in a set of painterly values was absorbed first at Gray's School of Art, Aberdeen (1964-69) then capped by three years at the Royal College of Art (1969-72) where the conceptual foundations of his work (above all) were challenged and strengthened. He was left with an adaptable and robust practice perfectly suited to his temperament and personality. His later professional teaching experience and exposure to contemporary art and to the masters of the past consolidated his allegiance to aesthetic and intellectual clarity. His titles again and again tell us that he is driven not only by the eye but also by the idea.

In the earliest works, a mode of address (what in a writer would be called a voice) is already apparent. It involves the intensity with which the image is realized, which expresses powerful feeling, and the countervailing objectivity of form that endows it with particularity. It involves, too, his relationship to his subject matter, and a constant awareness of the act of painting (all serious painting is about painting). Out of this complex the painted image emerges, endowed with the compelling clarity that only a painted world can possess. This is what the artist means by ‘imagist', his favoured term for himself and the artists with whom he has most affinity.

The exhibition is arranged in sections that correspond to four broad periods in Alan Robb's oeuvre. In the first, the paintings (in acrylic, which he began to use in 1971) are based on collaged imagery derived from comic-book and other graphic sources. Two key works of this period, A Positive Step Towards the Negative (1973-74) and Could be Continued (1977) are organized into disrupted narrative sequences by playing with a variety of framing devices, cuts, close-ups and text. Though aligned with Pop Art, they are not naïve paeans to popular culture. Their influences are less from artists like Peter Phillips, star-struck by Americana and the new consumerism, and more from the cerebral and ironical work of Marcel Duchamp, Richard Hamilton and, perhaps above all, Oyvind Fahlstrom, who still stands high in his personal pantheon. One sly sign of this in works of this period are hands that reach into the picture from ‘outside'. Metonyms for the artist, they are reminders that a painting is not ‘given' but is the result of a process, a process in which the viewer too has their part.

Alan Robb's painting begins as, and remains, an art of ideas. By the late 1970s, in paintings such as Clip Strip (1978-80) and My Move (1980-81) the essence of the comic-inspired language remains but the page-like paradigm of the early compositions has broken and condensed into islands of intricate figurative and mechanical allusions among which the eye seizes on the occasional recognizable detail. By the time of Toys for Boys (1983-85) the figurative element is dominant although still juxtaposed with collage-derived compounds. An important impact on its evolution was a visit to Chicago in 1984, on which he saw the work of artists associated with the Hairy Who and Chicago Imagist groupings, including Roger Brown and Jim Nutt; and in the work of Art Green especially he found many parallels with his own ideas.

Alan Robb's painting begins as, and remains, an art of ideas. By the late 1970s, in paintings such as Clip Strip (1978-80) and My Move (1980-81) the essence of the comic-inspired language remains but the page-like paradigm of the early compositions has broken and condensed into islands of intricate figurative and mechanical allusions among which the eye seizes on the occasional recognizable detail. By the time of Toys for Boys (1983-85) the figurative element is dominant although still juxtaposed with collage-derived compounds. An important impact on its evolution was a visit to Chicago in 1984, on which he saw the work of artists associated with the Hairy Who and Chicago Imagist groupings, including Roger Brown and Jim Nutt; and in the work of Art Green especially he found many parallels with his own ideas.

In Toys for Boys, the hitherto shallow pictorial space deepens and selected forms, especially the figures of the cowboy and the Action Man, acquire a new three-dimensionality. While capturing the vivid life of toys in a boy's imagination, the painting is also a backward look from the distance of adulthood, the warmth of its empathetic connection to childhood countered by the knowledge that it is unreachable. The symbol of this is the poised yet isolated figure of the headless Action Man, which stands (phallic but deprived of the power of action) in the paradoxical position of a sightless witness. Throughout the artist's work, the toys, figurines, ex-votos and models that are such constant presences have this double effect, to connect and distance at one and the same time.

By the time of Who's Afraid of the New Technology (1987) the figurative elements retain their identity in a complex space of transparencies and overlaps that the artist has described as being like a stage set. The title alludes to the endlessly repeated (and misguided) assertion of painting's redundancy in the face of technological progress, its irony stemming from the artist's enjoyment in translating digital effects into the language of paint (much as, before, he had qualities of print). In retrospect, the filling out of space and form in Who's Afraid of the New Technology and other works around this time was the harbinger of the next distinct phase of his work. The major painting of the end of the ‘eighties was Cool House (1989-91) in which he returned from acrylic to oil paint, a more flexible medium for creating the qualities of space, light and form that increasingly engaged him. With its imagery rooted in memory, Cool House evokes an almost surreal atmosphere of dreamlike precision and stasis, but it stands isolated in his oeuvre because the prolonged search for its final form ultimately led him to explore the foundations of his art in the neo-classical tradition. Thus, the figure, landscape and still life became his preoccupations during the 1990s.

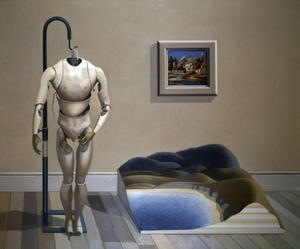

The central thrust of this second period received its fullest treatment in two large paintings, I Am What I Know (1993-94) and I Live Now (1998-2000). Though separated by around five years, they are unquestionably siblings. Both are ambitious summations of the painter's knowledge and craft, and declarations of allegiance to the ideal of formal and conceptual clarity. In these and others in which the classicising tendency is apparent, models are often the subject matter. For example, in the austere I Am What I Know, three sorts of model are pictured: a simulacrum (the full-size lay figure), an exemplar or ideal (the ‘Poussin' on the wall, a detail taken from Landscape with the Funeral of Phocion) and a replica (the landscape section). The painting too is a model, a representation of the artist's world pared down to bare essentials.

The central thrust of this second period received its fullest treatment in two large paintings, I Am What I Know (1993-94) and I Live Now (1998-2000). Though separated by around five years, they are unquestionably siblings. Both are ambitious summations of the painter's knowledge and craft, and declarations of allegiance to the ideal of formal and conceptual clarity. In these and others in which the classicising tendency is apparent, models are often the subject matter. For example, in the austere I Am What I Know, three sorts of model are pictured: a simulacrum (the full-size lay figure), an exemplar or ideal (the ‘Poussin' on the wall, a detail taken from Landscape with the Funeral of Phocion) and a replica (the landscape section). The painting too is a model, a representation of the artist's world pared down to bare essentials.

Models are intermediate objects through which ideas can be distilled into forms and vice versa. These twin aspects are present, for example, in smaller works such as Lonely Beach (1995), La Rotonda (1997) and the bronze, Corrie (1998), but in I Live Now, models also serve an autobiographical purpose. The artist pictures himself standing beside a full-scale version (on his studio easel) of Landscape with the Funeral of Phocion, proffering towards the viewer a model of Palladio's Villa Rotonda, while carrying the accoutrements for a day's open-air painting. Poussin (again) and Palladio give the artist his ideals of intellectual clarity, formal resolution and proportion, derived (as the painting gear suggests) from the observation of nature. The painting acknowledges the standard set by his admired predecessors and the enormous difficulty of even approaching the ideal, but it is lent an ironic humour by the artist's self-knowledge. Yet, engaging his viewers with a direct gaze that implicates us too, he could well be saying, “I at least have made this painting. What have you done?”

The paintings of this period might seem an anti-modern volte-face in comparison to the earlier works but this is not so; they are connected by the same ordering instinct, the same need to crystallize the idea in a precisely realized image - a permanent form - and by the same questioning of the nature of the painter's art. It is the last that ultimately distinguishes I Live Now, with its nested complexity, self-awareness and seriousness of purpose. In every way, it is the capstone of the period. There may be other works as serious in recent Scottish art but none more, because the artist stakes everything on it: it is the credo of a lifetime's commitment. And yet, as all such statements must, it posed a question: what now?

It took some time for the answer to that question to reveal itself. In several small works painted towards the end of the ‘nineties, what in retrospect can be seen to be a new theme tentatively declares itself: Catholic iconography and its place in the visual tradition that had engrossed him for a decade. However, sacred imagery only began to move to the centre of his thoughts after a visit in 1998 to Rio de Janeiro, on which he saw the dramatically lit anthropological displays of the Museo de Folclore Edison Carneiro. They aroused his fascination with Afro-Brazilian folklore and with the pantheon of Candomblé, an amalgam of West African and Christian cosmologies. The displays themselves indicated a way ahead from the spartan aesthetic of the 1990s, which, when put into practice, allowed him to preserve the core values of his painting while expanding its range of content and expression. He entered a theatre of the psyche. The stage is an apposite metaphor, given the theatricality of the popular artefacts of Candomblé, the figurines of its major and minor deities and spirits. The iconography of this syncretic faith of the people, which attracted him not least by its compelling mixture of the familiar and the unfamiliar infused with the vitality of street culture, became his primary inspiration for most of the next decade.

It took some time for the answer to that question to reveal itself. In several small works painted towards the end of the ‘nineties, what in retrospect can be seen to be a new theme tentatively declares itself: Catholic iconography and its place in the visual tradition that had engrossed him for a decade. However, sacred imagery only began to move to the centre of his thoughts after a visit in 1998 to Rio de Janeiro, on which he saw the dramatically lit anthropological displays of the Museo de Folclore Edison Carneiro. They aroused his fascination with Afro-Brazilian folklore and with the pantheon of Candomblé, an amalgam of West African and Christian cosmologies. The displays themselves indicated a way ahead from the spartan aesthetic of the 1990s, which, when put into practice, allowed him to preserve the core values of his painting while expanding its range of content and expression. He entered a theatre of the psyche. The stage is an apposite metaphor, given the theatricality of the popular artefacts of Candomblé, the figurines of its major and minor deities and spirits. The iconography of this syncretic faith of the people, which attracted him not least by its compelling mixture of the familiar and the unfamiliar infused with the vitality of street culture, became his primary inspiration for most of the next decade.

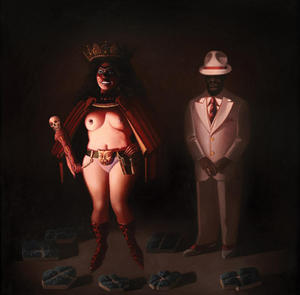

He again followed what is clearly his established practice, by tracking (that is, defining and discovering) his subject through a series of smaller works and studies that congregate around a few larger paintings, the major statements of the theme. Among the latter are Zé Pelintra, St Jorge and his Dragon (2001-04), Pomba Gira Queen of the Seven Crossroads and Zé (2004-05) and Brasil: The Taste of Blood (2005-08). Based on figurines bought in specialist shops, his cast members retain the qualities of their originals and their characters in the supernatural dramas that they enact (St Jorge resolute in his lacy and feathered finery; Zé, the guide and friend of the poor, is a sharp-suited ‘malandro'; the voluptuous and dangerous Pomba Gira is the embodiment of female sexual power). They are imagined dramatically lit in indeterminate spaces, like the visions or premonitions of a dreamer.

Among the smaller works of this period are watercolours of Exu, Yemanja, Pomba Gira, Zé, St Peter, St Lucy, Venus and ex-voto figures, several originating as studies for the larger works. Shown first in 2005 as a group of twelve, the series has grown to thirty in number, collectively entitled Sacred and Profane (2005-10). For a believer, the figure of a deity or lesser spirit is an emanation from a higher reality, like a battery charged with the latent power of the miraculous. Appropriated by the artist, it may be re-imagined and incorporated into his world. This begs the question, why? The answer is that the chthonic personages of Candomblé offered a mythos that enabled him to enter a new territory of ‘depth imagery' while their cheap and gaudy representations, a living part of the everyday Brazilian scene, returned him to popular culture as his subject matter after the long exploration of his high art European roots. His borrowings are not treated simply as appropriations but as paradigms of globalizing culture, Afro-Brazilian in their specificity but universal in general and with an iconography that, changed in little more than names and dress, can be found in repositories and shrines across Europe.

Pomba Gira, Zé and others recharged the side of his art that has always complemented the search for formal resolution. If art requires internal tension, then in Alan Robb's painting it comes from that between sensuous subject matter and formal discipline, between immersion and distance, feeling and concept. His work draws much of its energy from the contest of the forming impulse with its libidinal and myth-haunted underworld. This is clear in the paintings that spring from his encounter with Candomblé, which, despite all evident differences, cast a beam of light back onto his earlier work, even to the earliest shown here, in which the canvas can barely contain everything that his imagination wants to project onto it, or the formal structure the energies that threaten to burst through the binding black outlines.

Pomba Gira, Zé and others recharged the side of his art that has always complemented the search for formal resolution. If art requires internal tension, then in Alan Robb's painting it comes from that between sensuous subject matter and formal discipline, between immersion and distance, feeling and concept. His work draws much of its energy from the contest of the forming impulse with its libidinal and myth-haunted underworld. This is clear in the paintings that spring from his encounter with Candomblé, which, despite all evident differences, cast a beam of light back onto his earlier work, even to the earliest shown here, in which the canvas can barely contain everything that his imagination wants to project onto it, or the formal structure the energies that threaten to burst through the binding black outlines.

After the painting of Brasil: The Taste of Blood, another phase of change began to gather momentum, bringing the artist's work into the present. He also shifted medium from oil back to acrylic, and to the layering approach that acrylic requires. If it is possible to characterize this fourth and latest period, it is another sort of syncretism, one that draws on all the strands of his previous work, a field of play more open than any he has allowed himself before. Indeed, the notion of ‘phases' begins to break down as ideas are reimagined and works repainted alongside (and as part of) new developments. This is what ‘a painted world' means: not only a practice of painting that can extend its formal language, but also that, over four decades, the artist has created an iconographic world large enough to become its own subject, generating new content and ideas from itself. The progress of his work could be described as a spiral of simultaneous return and advance.

This orbital movement has grown out of his practice of working on paintings over extended periods of time. Some have been exhibited in different states, not as works in progress (as his old mentor Peter Blake does) but as finished, though later he took them up again and pushed them to new, very different, conclusions. He did this, for example, with Cool House between 1989 and 1991 (recording its several incarnations). Among more recent works, Zé Pelintra, St Jorge and his Dragon was transformed in 2007 and Pomba Gira Queen of the Seven Crossroads and Zé in 2008. While these were rethought within the iconographies of their respective phases, two others show the practice of revision contributing to the latest transition. Clip Strip was begun in 1978, exhibited in 1979 and radically changed in 1980. There it rested until being repainted in 2011 into what is substantially a new work, the artist using the visual language of thirty years before and finding in it still untapped resources. However, the centrepiece (so far) of the newer work, is the large Brother David's Last Mission, begun in 2008 and first shown in the Royal Scottish Academy in 2009. Reworked, with new additions, in 2010-11, it signals an exit from the glamour of Candomblé's dark theatre.

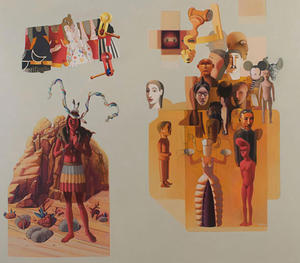

In it, pictorial space is no longer stage-like but a shallow field. As in his 1980s' work, it is a painted space, not an illusionistic one, in which images of different scale find their place. The main figures are, on the left, a Caboclo (a Candomblé spirit, here in the guise of a Native American) posed against rocks derived from DC Comics illustrations, and, on the right, the Catholic missionary, Brother David, surrounded by a company of heads and figures, some being ex-votos (the source of Brother David) and some of more personal significance. Among them is an African mask from the Dundee Museums collection and heads of Barbie and a schematic Mickey Mouse (which alludes to Michael Sandle's sculpture, A Twentieth Century Memorial). A cluster of colourful toys and children's costumes derived from pre-Carnival displays in Rio markets, appears above the Caboclo (and again in the newest painting in the exhibition, St. Lucy… ?.). The festivities of Carnival, the association of Caboclos and ex-votos with healing, and the consoling power of art itself unite the picture thematically. It radiates a feeling of well-being, the state that the Greeks called eunoia.

In it, pictorial space is no longer stage-like but a shallow field. As in his 1980s' work, it is a painted space, not an illusionistic one, in which images of different scale find their place. The main figures are, on the left, a Caboclo (a Candomblé spirit, here in the guise of a Native American) posed against rocks derived from DC Comics illustrations, and, on the right, the Catholic missionary, Brother David, surrounded by a company of heads and figures, some being ex-votos (the source of Brother David) and some of more personal significance. Among them is an African mask from the Dundee Museums collection and heads of Barbie and a schematic Mickey Mouse (which alludes to Michael Sandle's sculpture, A Twentieth Century Memorial). A cluster of colourful toys and children's costumes derived from pre-Carnival displays in Rio markets, appears above the Caboclo (and again in the newest painting in the exhibition, St. Lucy… ?.). The festivities of Carnival, the association of Caboclos and ex-votos with healing, and the consoling power of art itself unite the picture thematically. It radiates a feeling of well-being, the state that the Greeks called eunoia.

While Brother David's Last Mission has one foot in the Brazilian mise-en-scène but moves beyond it (and does the title not suggest that it is the artist who is moving on?) in some ways it represents a return to the modus operandi of his early works, with juxtapositions and layering of diverse imagery. It also combines various touchstones from across the artist's career, from popular culture, comic-book graphics, religious iconography and high art, out of which he has synthesized his work. This is a more relaxed Alan Robb, more at ease with himself and with painting than at any time since the 1980s. The artist's confidence in his own territory can be seen in the inclusion of ‘unfinished workings' among the figures that surround Brother David, something he has not permitted himself before. Emblems of painting as a slow, thoughtful, concentrated, additive process, they are a new means of sustaining the dialogue with making that is characteristic of his concept of painting as an art.

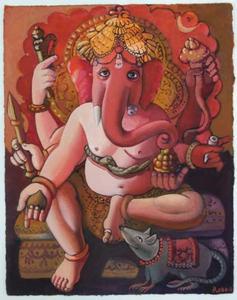

If the final question is where his painting is headed, it is clear that he now treats his whole oeuvre as an open book. It may be that something from the formal visual language of the mid-1980s will find a place, while, on the side of new beginnings, a hint may be found in The Lord Ganesha (2011). A small watercolour that has joined the set of Sacred and Profane, it is one fruit of a recent engagement with Indian art, architecture and Hindu iconography inspired by new family connections and a visit to India in late 2010. What these and other developments may lead to is, as yet, unknowable. All that can be said for now is that painting goes on.

If the final question is where his painting is headed, it is clear that he now treats his whole oeuvre as an open book. It may be that something from the formal visual language of the mid-1980s will find a place, while, on the side of new beginnings, a hint may be found in The Lord Ganesha (2011). A small watercolour that has joined the set of Sacred and Profane, it is one fruit of a recent engagement with Indian art, architecture and Hindu iconography inspired by new family connections and a visit to India in late 2010. What these and other developments may lead to is, as yet, unknowable. All that can be said for now is that painting goes on.

Euan McArthur