IN THE MIND'S EYE

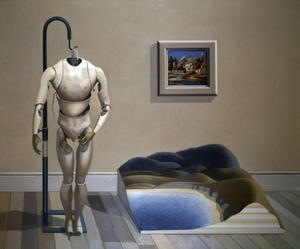

In one of the largest recent works, I Am What I Know (1993/94) all embiguities are dispensed with. Three objects are depicted naturalistically in the empty studio; the lay-figure, the landscape model and, on the wall behind, a picture. The picture is based on a detail from Poussin's Landscape with the Funeral of Phocion. Each is separated from the other in an image of absolute stasis, their arrangement not wholly unrelated to the tabulation in Empty Beach with Purist Symbols. This studio seems to be the most hermetic of environments, a world of detachment, of form and essences in which the artist works in the daunting presence of the past. I Am What I Know is perhaps the image in which Alan Robb confronts the monumental tasks of the artist, the near impossible task (as Harold Bloom might say) of challenging tradition to create a place for oneself within it. The title could hardly make this clearer: Sooner or later every artist must meet the past masters who live in his imagination if they want their work to prosper.

In one of the largest recent works, I Am What I Know (1993/94) all embiguities are dispensed with. Three objects are depicted naturalistically in the empty studio; the lay-figure, the landscape model and, on the wall behind, a picture. The picture is based on a detail from Poussin's Landscape with the Funeral of Phocion. Each is separated from the other in an image of absolute stasis, their arrangement not wholly unrelated to the tabulation in Empty Beach with Purist Symbols. This studio seems to be the most hermetic of environments, a world of detachment, of form and essences in which the artist works in the daunting presence of the past. I Am What I Know is perhaps the image in which Alan Robb confronts the monumental tasks of the artist, the near impossible task (as Harold Bloom might say) of challenging tradition to create a place for oneself within it. The title could hardly make this clearer: Sooner or later every artist must meet the past masters who live in his imagination if they want their work to prosper.

His most recent work could be seen as being essentially a concentrated engagement with the tradition of still life. It is not surprising that still-life should have emerged as a subject in Alan Robb's work, given the formal and concrete values, the mixture of observation and ideation which still-life entails. Several have been painted in recent years, ranging from the opulently decorative Tropical Fruits, Rio (1991) to the austere Faraway Fruits (1995) in which the full forms of the fruit glow against a velvet-background. The lucent quality of this work is achieved by a wet-into-wet oil technique which enhances the richness of colour while allowing great subtlety of tonal variation, a technique employed in all of the most recent paintings, which echoes the soft blends of colour in the earlier works.

Since 1992 Alan Robb has made several paintings which have placed the landscape model in the foreground. One, entitled Empty Beaches with Model Tanker, is similar to Empty Beach with Purist Symbols in that a series of images are show above one another. The landscape relief model is the principal object of attention. At the top, two such models appear among stones and seaweed; in the middle, another model is shown in the studio in front of a painting, and at the bottom a third is shown with a model tanker. The painting contrasts and interweaves the real, the model and the concept within the larger representational fiction of the painting itself. In several of the recent works the simulacrum, the intermediary through which Alan Robb ahs always approached the real, becomes painting itself. They incorporate paintings in painting, or themselves could be paintings of paintings.

They have, however, more than simply formal content. They are not only investigations of the painter's reality or vocabulary alone. The clearest indication of this is given in Calm Before the Storm (1992). A foreground of stones and seaweed (panted with the precision of a studio arrangement) occupies most of the image. Beyond, several tankers pass on the horizon. The then recent Braer disaster in which a tanker using a convenient but dangerously narrow channel to the Atlantic ran aground, contaminating the clean waters of Shetland, is a looming reference beyond the image. Similarly in the other Empty Beaches paintings, there is an underlying concern with the environment. Empty Beach with Painting (1995) for example, brings the reference close to the artist's home, to the rural landscape of Fife. The pattern of ploughing and the rolling forms of the hills, recall Grant Wood's paintings of American farmlands in the 1930s, but the unnaturally sharp and resonant green of the fields records a contemporary factor: the ubiquitous application of nitrates to enhance crop production.

They have, however, more than simply formal content. They are not only investigations of the painter's reality or vocabulary alone. The clearest indication of this is given in Calm Before the Storm (1992). A foreground of stones and seaweed (panted with the precision of a studio arrangement) occupies most of the image. Beyond, several tankers pass on the horizon. The then recent Braer disaster in which a tanker using a convenient but dangerously narrow channel to the Atlantic ran aground, contaminating the clean waters of Shetland, is a looming reference beyond the image. Similarly in the other Empty Beaches paintings, there is an underlying concern with the environment. Empty Beach with Painting (1995) for example, brings the reference close to the artist's home, to the rural landscape of Fife. The pattern of ploughing and the rolling forms of the hills, recall Grant Wood's paintings of American farmlands in the 1930s, but the unnaturally sharp and resonant green of the fields records a contemporary factor: the ubiquitous application of nitrates to enhance crop production.

Empty Beach with Tanker (1995) is one of Alan Robb's most finaly poised images and perhaps the most complete statement in his recent work. Only the tanker and the landscape model are depicted, one above the other: Each casts its shadow on the flat background plane. The understated colour, tonalities and linear precision sustain a beautifully-modulated harmony of form and presence with great economy. The ideational character of the image is made clear. There is no closure of meaning in this painting, because both images are allowed to go beyond conscious intention. They are not symbols and their relationship is not limited by any matter-of-fact correspondences. The viewer is engaged by their illusory objectivity, the deceptive quiddity of the presences which they manifest. In this ligh, the other paintings in the series can also be seen to embody the free pleasure of the imagination at play as much as they are investigations of the intangible essences of painterly representation. The reduction of means and context and the merging of idea and object in an expressive minimum has perhaps found its current bench-mark in the small Lonely Beach (1995). The image is reduced to the model alone, located in the darkened space of the studio from which, like a barely perceived visual thought, it has somehow condensed.