I LIVE NOW

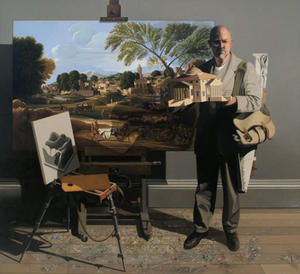

The summation of this body of work came in 1999 with the completion of l Live Now, shown (with others discussed here) in the artist's second solo exhibition at East/ West just prior to the millennium. In this large painting (two-thirds life size, every element accurately scaled by computer imaging) the artist appears in his studio with several objects that embody this artistic world. Though he is shown burdened by the equipment of the artist who works outdoors, this painting is manifestly a studio construct. Evidently whatever the source of his material it is all interiorised in his synthesising imagination and through the nature of his painterly concerns. On the studio easel is the artist's version of Poussin's The Body of Phocion being carried out of Athens, and in his hands is a model of Palladio's Villa Rotonda, the perfection of neo-classical architecture. These may be taken to represent his chosen masters, but this is far from a straightforward homage, and even less the confident statement of an artistic credo it might seem to be at first glance. In fact it is both elegiac and a work of deep irony, in which irony has a constructive purpose, that of expressing the problematics of an artist's self-conception of his relationship to tradition. The title is taken from a passage in a Robertson Davies novel, in which a young woman describes her sense of belonging simultaneously to the present and the past, a dichotomy that cannot be resolved but must be lived.

The summation of this body of work came in 1999 with the completion of l Live Now, shown (with others discussed here) in the artist's second solo exhibition at East/ West just prior to the millennium. In this large painting (two-thirds life size, every element accurately scaled by computer imaging) the artist appears in his studio with several objects that embody this artistic world. Though he is shown burdened by the equipment of the artist who works outdoors, this painting is manifestly a studio construct. Evidently whatever the source of his material it is all interiorised in his synthesising imagination and through the nature of his painterly concerns. On the studio easel is the artist's version of Poussin's The Body of Phocion being carried out of Athens, and in his hands is a model of Palladio's Villa Rotonda, the perfection of neo-classical architecture. These may be taken to represent his chosen masters, but this is far from a straightforward homage, and even less the confident statement of an artistic credo it might seem to be at first glance. In fact it is both elegiac and a work of deep irony, in which irony has a constructive purpose, that of expressing the problematics of an artist's self-conception of his relationship to tradition. The title is taken from a passage in a Robertson Davies novel, in which a young woman describes her sense of belonging simultaneously to the present and the past, a dichotomy that cannot be resolved but must be lived.

The picture on the sketching easel (an actual work of the artist's entitled Corrie, also realised in bronze) echoes the Palladian villa and represents the imposition of form on the natural world, expressing the impulse to organise and humanise. The Poussin is the epitome of an organised, humanised world, an unrealisable ideal of harmony between man and nature. Here, it embodies a modern awareness of loss and separation from that ideal. It is a painting of a painting within a painting, which suggests both the pictured world's unattainability and the actual picture's remoteness from the artist. Like the Villa Rotonda, it can be present (in the artist's mental world) only by means of a simulacrum, a substitute or an approximation. This is an eloquent statement of nescience, the conditional and limited nature of knowledge, and of the inescapable subjectivity that enters the equation between artist and tradition.

But of course all is not lost. As Ezra Pound wrote, “error is all in the not done, all in the diffidence that faltered”. The artist has made the work, and with it made a declaration: I live now, not Poussin or Palladio. Beyond the uncertainties of history, the artist depicts the existential fact of his moment in time, his opportunity to make his statement. Either one falters or, as Pound also said, one makes it new, but in the full consciousness that one might succeed or fail in the judgement of others. The in-built ironies emerge with this perception. The deadpan allusion to Courbet's Bonjour Monsieur Courbet suggests that realism in art in the end is no different from idealism, both equally fictitious re-orderings of an endlessly elusive and impenetrable reality. It is also a joke against the artist and his ambitions, which resonates with his use of the Poussin. Phocion, who put honour above self-interest and was assassinated, was in death refused the grand tomb that was his by merit and buried secretly in an anonymous grave. Is the body of Phocion the artist's (all later artists') metaphorical body being carried out of that particular closed painterly paradise, or from the dream of history itself, represented by an idealised Athens that never existed? Or is it an image of every artist's fear of failure in the face of the great tradition of painting? Probably all of these. The artist's identification with Phocion is unmistakable: notice how his shadow-profile seems to peer at the wrapped corpse. Irony cuts deeper, too, in the conflation of the artist with St. Jerome, often depicted holding a model church. Then, too, the whole image was planned and compiled on computer, a digital illusion before being traditionally painted through many layers and revisions, a perverse process from a technologistic perspective but entirely fitting to the aims of the work. Aware of all these ironies, the artist stands in his self-created world, in his own words, with “mouth set firm, ...resolute in his position, which may be as foolish as Don Quixote”. Perhaps it is not irrelevant to add that he has considered the bronze Corrie for part of his own tomb. I Live Now presents a bold, declaratory face to the viewer, which on closer reading expresses (again in the artist's words) “the humour and the commitment” of his possibly quixotic position. It is one of the most complex, nested, meditations on the relationship between the artist, his medium and tradition in the history of Scottish art, and certainly the most complex of recent times.

Euan McArthur